05 Feb

2024

Examining the 2023 Year-End Report on the US Federal Judiciary

Chief Justice John Roberts recently released the 2023 Year-End Report on the Federal Judiciary, highlighting the evolution of technology within the general legal landscape and the Federal Judiciary specifically. In the report, Chief Justice Roberts discusses the judiciary’s hesitance to depart from longstanding methods and its measured approach to adopting technology. Artificial intelligence, in particular, receives a thorough review, as Chief Justice Roberts considers the opportunities and challenges for the justice system that arise from this powerful, emerging technology.

Recounting the justice system’s slow adoption of technology

Chief Justice Roberts expands on the transition from the inkwell to the typewriter; the evolution from the oversized, stationary computer to the personal mobile device; and the ongoing digital revolution that originated in the digitization of paper documentation and evidence through the Public Access to Court Electronic Records (PACER) system.

This digital revolution continued with the emergence of Case Management/Electronic Case Files (CM/ECF), which brought about a “seismic shift in efficiency,” allowing lawyers, law clerks, and judges to file pleadings and other court documents at any time, from any location. The digital revolution was further propelled by the COVID-19 pandemic, with courts shifting services online through remote and hybrid hearings and providing access to digital services.

Chief Justice Roberts emphasizes that artificial intelligence is simply the “latest technological frontier.” If we forego skepticism in favor of open-minded questioning, the continuous evolution of artificial intelligence technologies will introduce novel capabilities and possibilities that can enhance—not replace—existing legal practices and traditions.

The duality of artificial intelligence

On one hand, artificial intelligence can be regarded as the latest technological frontier, offering cutting-edge advancements that redefine the way legal professionals approach their work.

On the other hand, it is crucial to acknowledge that artificial intelligence, in various forms, has been present in the legal domain for a considerable time. Previous iterations of artificial intelligence have been applied to improve information processing, legal research, predictive analytics, and document discovery, thereby laying the groundwork for the current landscape.

The transformative shift lies in the extent of artificial intelligence integration into legal practices. What has changed is not just the existence of artificial intelligence, but the increased prevalence of various types of applications within courtrooms and other legal spaces.

The latest advances, especially the advent of generative artificial intelligence models like ChatGPT, mark a paradigm shift. Now, systems can generate human-like responses and create content, including text, audio, and more, thus influencing communication, analysis, and information processing. Other categories of artificial intelligence, such as the natural language processing model that powers speech-to-text conversion, have become common tools, that are not often associated with artificial intelligence.

Incorporating artificial intelligence poses distinct challenges in the justice system, which has always relied on the informed, balanced judgement of human professionals and trusted in the accuracy of legal submissions. Chief Justice Roberts illustrates these challenges, citing concerning examples of generative AI use, such as attorneys who leveraged ChatGPT to produce legal briefs that ultimately included incorrect case citations. Chief Justice Roberts also considers the possibility that judges will eventually become obsolete—a prospect he deems unlikely.

With such challenges in mind, how can and should artificial intelligence assist in the justice system?

Differentiating tools for efficiency from replacements for decision-making

If we paint all artificial intelligence technology with the same brush, we risk inhibiting beneficial progress for a system long beleaguered with delays and inequalities.

As such, it is critical to distinguish the different ways in which artificial intelligence-based technology is used. There are tools that enable court staff and attorneys to be more efficient, and then there are applications that branch into an abdication of judicial decision-making or—more broadly—legal decision-making.

While artificial intelligence-based tools that reduce rote tasks must still contend with cybersecurity threats, deepfakes, and biases, they do not introduce the serious epistemological questions or ethical issues that arise when artificial intelligence replaces human judgement. Chief Justice Roberts rightly asserts, “…legal determinations often involve gray areas that still require application of human judgment.”

While there is broad agreement as to the necessity of maintaining human oversight in legal decision-making, the discourse around artificial intelligence tends to focus on sensational, undesirable scenarios. In the process, the public overlooks valuable artificial intelligence applications—like automated courthouse scheduling—that have already improved previously time consuming and costly processes.

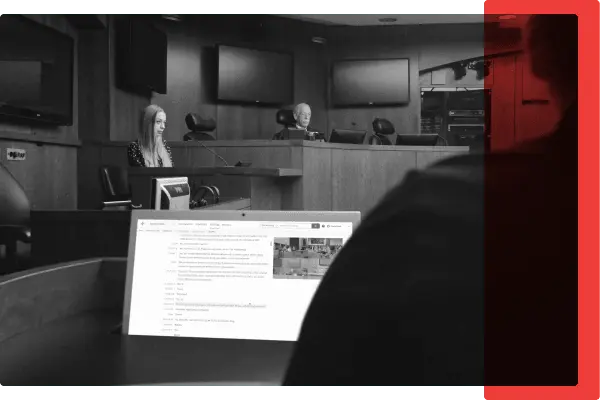

Emerging artificial intelligence applications, like speech-to-text transcription for courts, show overwhelming promise for enhancing efficiency and supporting access to justice. Right now, such speech-to-text platforms are in leading-edge courtrooms, producing rough draft transcripts of hearings in real-time. The transcripts sync with recorded audio and video of hearings, which allows participants to verify the accuracy of the written content and provides insight into tone and body language.

Compare this output to a traditional transcript, prepared by a stenographer, which is typically not available for weeks and consists solely of text. The draft transcript produced by technology offers far more information, instantly, at a fraction of the cost.

Chief Justice Roberts notes, “Machines cannot fully replace key actors in court. Judges, for example, measure the sincerity of a defendant’s allocution at sentencing. Nuance matters: Much can turn on a shaking hand, a quivering voice, a change of inflection, a bead of sweat, a moment’s hesitation, a fleeting break in eye contact. And most people still trust humans more than machines to perceive and draw the right inferences from these clues.”

It is evident we must continue to trust legal professionals to draw conclusions from these contextual clues, but it is also true that we can trust technology to accurately preserve this level of nuance for these legal professionals to revisit time and time again.

While speech-to-text transcription demonstrates broad utility, it is often feared as another attempt to eliminate people from the courtroom. This is not the goal, and it is important to remember that such technology is a tool to be used by courts, for the benefit of the broader justice system.

Chief Justice Roberts points to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, in which rule one “…directs the parties and the courts to seek the ‘just, speedy, and inexpensive’ resolution of cases. Many AI applications indisputably assist the judicial system in advancing those goals.” In essence, we have an obligation to explore artificial intelligence technology that enhances efficiency and increases access to justice.

Balancing caution with progress

The report rightfully emphasizes the importance of cautious implementation and the need for ongoing evaluation, particularly in ensuring fairness and avoiding privacy infringements and other significant concerns associated with artificial intelligence. Of course, education and digital upskilling by courts is needed to effectively implement safeguards for beneficial use.

A shift in the conversation around artificial intelligence would be beneficial: emphasizing its role as an informative tool rather than a complete replacement for human involvement in the justice system would reduce fear and skepticism. Trust in legal professionals remains essential, but advancements in digital recording systems and other artificial intelligence-based tools can ensure people can do their jobs better and litigants and other court participants can access justice services at much lower costs.

Indeed, courts have already undergone notable transformations in the realm of digitization. Chief Justice Roberts highlighted advances in electronic filing and case management updates as illustrative examples. Time and time again, society has been faced with new developments which have been analyzed, challenged, and ultimately integrated or rejected within existing structures and processes. Artificial intelligence has not been, and will not be, any different.

As Chief Justice Roberts said, “These tools have the welcome potential to smooth out any mismatch between available resources and urgent needs in our court system.”